Did you know that you can navigate the posts by swiping left and right?

DPRK - Part 6

24 Mar 2016

. category:

Travel

.

Comments

#DPRK

As promised, here are some haphazard reflective / summarizing thoughts about my week in North Korea. Apologies for the length of this post, I just have a lot of profound thoughts.

Tour Happenings and People

Fellow Travelers

As you might imagine, people heading to North Korea are not exactly your average traveler, and I had a great time getting to know some of the other people on our tour (surprising both Aaron and myself with how outgoing I was). There were several experienced travelers (at least one person was over 100 countries), and I’ve been seeing great pictures on my Facebook feed recently from all over the world while I’m stuck in classes… Unsurprisingly, the people on the tour were also quite well-informed about the world. I probably had more cogent discussions about Trump this week than any other (they mostly began with foreigners asking me what the hell is wrong with America). Interestingly enough, the tour also included a lot of folks in the tech sector, I’d say around a third. Which I guess makes some amount of sense given job flexibility and income to travel like this, but it was still unexpected.

There is definitely a group of global travelers that have friends all over the world, with couches to crash on no matter where they are. Maybe this trip is my first venture into that community! Thanks to everyone on the tour for a great time.

Interactions with Locals

This is perhaps the question I’ve received most since returning: did I really get to talk to any locals? Aside from our three guides and then other local guides and waitresses, the answer is basically no. The closest we got was waving to schoolchildren while on the bus and walking about, and also that picture I took with the adorable child on the subway:

While the tour wasn’t as strict as we had anticipated, we still weren’t given free reign to speak to locals, and even if we had, I’m not sure I would have taken the risk to have interesting or profound conversations. And of course, given the language barrier, it may not have even been possible. This is definitely unfortunate: I would have really loved the chance to have an honest and frank conversation with locals (especially the children). But the tour is designed for this to be impossible, and taking unnecessary risks to speak with Koreans didn’t seem like a good idea. Especially as unmonitored activities really were still forbidden. For example, Albert at one point tried to buy something from a local food stand, and our driver ran over to tell him that was not okay.

How Real Was It?

This question was at the back of our minds the whole time, how much of what we were seeing was a charade? The first thing to realize is that even if everything we saw (shoppers at the department store, children on school tours, weddings, etc.) was real, we still did not receive anywhere near a holistic picture of North Korea. Just living in Pyongyang is a mark of favor in the DPRK, with the standard of living there being much higher than the rest of the country. I’ve even read that families with outwardly disabled children are sent away from the city. The DPRK is battling malnutrition, tuberculosis, and a host of other problems. But we were kept well away from even having the chance to see that side of the country.

There were also parts of our itinerary that did seem constructed. For example, a ridiculous number of beautiful wedding parties seem to follow us wherever we went, from Kim Il Sung’s birthplace to the Mansudae monument:

In addition, the other “customers” in the department store seemed to be gone when Aaron and Albert returned an hour to pick up a couple more things, and the number of bowlers at the bowling alley markedly decreased right around us leaving. It’s impossible to know if these were all just coincidences noticed by my paranoid self. Another perfectly reasonable explanation is that there just isn’t that much local demand for such luxury services. After all, we almost never saw locals in the various restaurants or bars that we frequented.

I do believe that every single scene we saw could have been constructed or at least sanitized in some way given that our itinerary was fixed well in advance. It would’ve been simple things: on our visit to the DMZ all poor neighboring villagers being told to stay out of their fields and off the roads. Work units could have “chosen” to visit the Mausoleum on the same day as us wearing their very best. And officials could have removed any unsavory looking characters from the subway for the one hour we were there. I’m not necessarily saying that this did occur, especially with some of the more logistically difficult events like the subway. But, a highly authoritarian and centralized state like the DPRK certainly has the capacity for making these things happen. And given the craziness of the regime / similar situations from China and the Cultural Revolution…

One moment in the trip did lead me to believe that our experiences were constructed at least a bit. We made a random stop, I think in Sariwon City but I’m not sure, and I had just remembered that we brought some Lindt truffles to give to children. We walked off the bus to meet some, when our guide Mr. Pang pulled us back. Apparently, tour groups had just recently started making stops at this location or something, so perhaps not everyone had been given the proper directives regarding foreigners? They also might have just been more wary because this wasn’t in Pyongyang, who knows.

How Restrictive Was It?

An article was just published in the NYTimes which paints tourism in North Korea as crazy restrictive. And I think the portrayal of events was probably accurate in 2009, but it’s significantly more relaxed now. We spent much of the week joking around with our guides, and as I mentioned before, they didn’t even look through my photos on the way out of the country or search my bag (to the best of my knowledge). It’s definitely not anywhere close to freedom, but it was much more relaxed than we expected and certainly more so than the article makes it seem.

Our Guides

Before leaving, we were told by the Young Pioneer folks that we would be joking with our guides by the end of the week, something I didn’t quite believe. But it really was true. Throughout the week, our guides had casual conversations with us, and made jokes. Ms. Kim started calling me “didi” (Chinese for little brother). She also made a couple of jokes about keeping my passport so that I couldn’t leave the country. While I still laughed, I found those less funny…

Statements by Guides / Sentiments of North Korean People

Our guides were the only North Koreans that we were truly able to dialogue with, so their statements are unfortunately the only thing we really have to go on. Given that they’re working in an official capacity, I presume their statements hew closely to the official positions of the regime and therefore what most North Koreans are told to believe.

Perception of the US

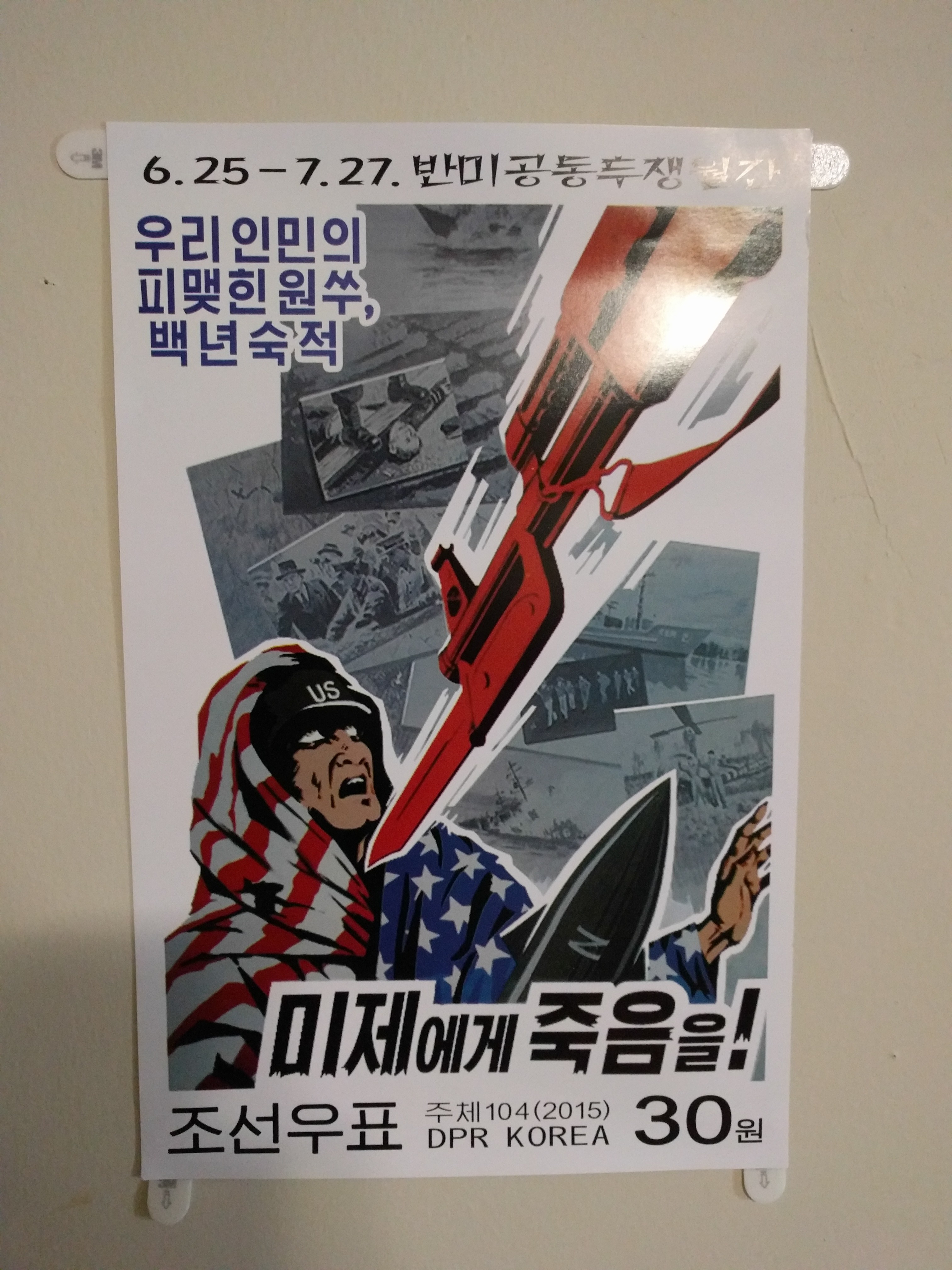

There was quite a bit of anti-US propaganda and sentiment, especially at the DMZ and Fatherland Liberation Museum (see previous blog posts for some good quotes). In addition, there was ample opportunity to purchase anti-US postcards and posters, like this one:

though these seem geared for the tourist market, as we mostly saw more generic propaganda about the Kims and hardwork in Pyongyang. I don’t remember who it was, but I think it was one of the guides who said that North Korea hates the US government but not the people. I certainly didn’t feel that there was any hostility from our guides (though of course they’re paid to be nice to us). But again, the number of anti-US statements said the various local guides we spoke to was quite interesting. I wouldn’t say flat out to anyone that I hate even their government.

The Division of Korea

Throughout our trip, the guides spoke at length about the painful division of Korea and the suffering of the Korean people. Even though it likely means the end of the regime, reunification was loudly proclaimed in both rhetoric and physical monuments. Our guides spoke of a Korea united by one language, one culture, one blood, but cruelly split by foreign powers (though I perhaps wouldn’t use the same language, I think this has a lot of truth in it).

The guides also talked about how, because of the split, North Korea is always in a very tense state, making them more sensitive than citizens from other nations. Ms. Kim even asked after our trip to the DMZ if we had felt safe while there. It just seemed like such a strange question to us, because we at no point felt anywhere near danger while at the DMZ (or the whole trip, for that matter). It’s not clear to me if this was because she personally felt unsafe while so close to South Korea, or because she thought foreigners would be alarmed by the North Korean soldiers who surrounded us.

Perceptions of their Leaders

Mr. Kim repeatedly said that their leaders “devoted their everything” to the Korean people, and that all Korean people genuinely respect their leaders. This was used to stress the importance of the various rituals such as bowing, the implication being that lack of conformity was also disrespectful to the Korean people at large and not just the Kims. Perhaps this was calculated, as the KITC knew that stressing respect for Kim Jong Un wasn’t going to be very effective.

Within Korea, it seems that love for Kim Il Sung is the most prominent. After all, his birthplace has been turned into a sacred and protected national site. And I heard his birthdate so many times that I’ll probably never forget it (April 14, 1912 if you’re curious). Now this may be because Kim Il Sung’s time was further in the past. But also, I think he occupies a better place in the North Korean consciousness, being the one who liberated Korea from the Japanese and presided over a more economically prosperous era compared to his son.

Somewhat surprisingly, Mr. Kim did acknowledge the difficulties experienced under Kim Jong Il, citing shortages of food, a lacking of electricity, and fuel for factories. Of course, this is an extreme under-exaggeration of a famine that killed hundreds of thousands of people. And his next sentence proclaimed that Kim Jong Il defended and led the revolution.

In the US, I think people often throw around terms like “supreme leader” jokingly, but in North Korea this really means something. And so do the other titles, Eternal President, Eternal Chairman, Marshal, etc. These names reflect an immense and powerful personality cult, the sustaining of which into the 21st century is, though terrible, quite impressive. It’s hard to know how North Koreans truly feel about their leaders. But in outward action, they are incredibly devoted. For example, every citizen above a certain age wears a pin of the supreme leaders above their heart.

Concluding Thoughts

This really was an incredibly fascinating week in an even more fascinating country. I feel like I’m supposed to have some profound thoughts here. Perhaps it should be what Mr. Kim said, that there are fundamentally good people everywhere, whether in North Korea or the United States. Or maybe it’s the realization that political oppression isn’t a physical feeling, that everyone we saw in Pyongyang seemed to live an outwardly very normal life. But for a nation with as tortured a past and a people as North Korea, I don’t think either of these are good enough. Really, all I can say is that if you’ve read this far, please keep reading and thinking about the country and perhaps how to improve the situation there. Before going, I personally read: Nothing to Envy and North Korea Confidential, as well as The Orphan Master’s Son. Going forward, I’ll be doing more research about how individual people can improve the situation on the Korean peninsula, and hopefully find a worthy cause for this trip’s matching charity donation.

Finally, writing these posts is a bit weird, in that I’m basically talking to the void. Please send me an email or message if you want to ask further questions / tell me I’m crazy / etc.